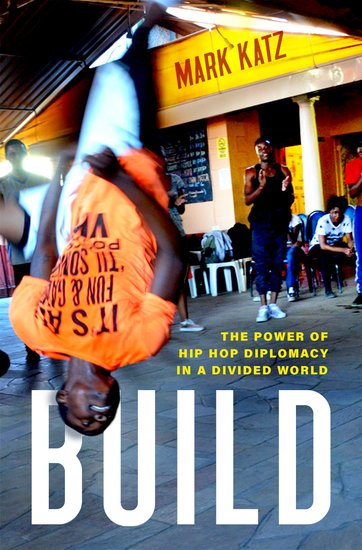

Mark Katz - Build: The Power of Hip Hop Diplomacy in a Divided World

Written by Chi Chi Thalken on November 14, 2019Mark Katz is Professor of Music at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, best known for his previous two books, Capturing Sound and Groove Music. Since publishing Groove Music in 2012, Katz went on to develop a cultural diplomacy program through the U.S. Department of State called Next Level. He now presents his experiences with that program and a larger look at cultural diplomacy in his latest book, Build: The Power of Hip Hop Diplomacy in a Divided World.

As Katz spells out in the book, the history of cultural diplomacy, specifically with music, goes back much further than Next Level, with jazz artists like Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington being sent abroad by the State Department in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Hip hop didn’t really get incorporated into the mix until the early ‘00s, specifically in the wake of 9⁄11, when groups like Ozomatli got involved and performed abroad on behalf of the U.S. government. In 2013, Katz found himself in the position of being contacted by the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, or ECA, who awarded him a grant and essentially charged him with re-launching the efforts of hip hop diplomacy on behalf of the State. Over the course of the book, Katz discusses a few different aspects of this experience. One is the history and function of musical diplomacy like this, which operates in this weird in-between space where a lot of people don’t even realize that it’s happening. By that I mean that our government is so large, that people that might be upset about hip hop diplomacy don’t even realize that this is a part of the U.S. budget. This is also the reason that artists like One Be Lo are able to involved – since they aren’t traveling and performing with anyone closely tied to the President or Congress, they are given the freedom to perform their music without fear of censorship from the U.S. Government (the local culture of where they are performing is something they have to consider, however). As a result, since they perform music that speaks truth to the power that they live under, they are able to connect more sincerely to the artists and audience members they meet abroad. Katz does discuss at length the weird tension that exists in this space, with what he describes as a “subversive complicity.” He also goes into detail about the ways in which different cultures had to be navigated, and how different musical languages were able to cross cultural divides that spoken language couldn’t. Over the course of the book, Katz is tasked with the difficult assignment of relating his personal experience of working with Next Level and traveling the globe with hip hop musicians, but also taking a step back and trying to provide an analytical framework and historical context for what is happening. It’s a difficult balance, and while it’s not always perfect, it ultimately works pretty well.

Build isn’t necessarily a foundational text that way that Groove Music is, but it does shed light on an aspect of the world that you’re probably not aware of. I know I came across multiple musicians through the course of the book that I knew but had no idea about this particular aspect of their career. It’s an interesting discussion to be had, and Katz does a good job of shedding light onto the world of hip hop diplomacy.

| Title: | Mark Katz - Build: The Power of Hip Hop Diplomacy in a Divided World |

|---|---|

| Label: | Oxford University Press |

| Year: | 2019 |

| Rating: | 8/10 |